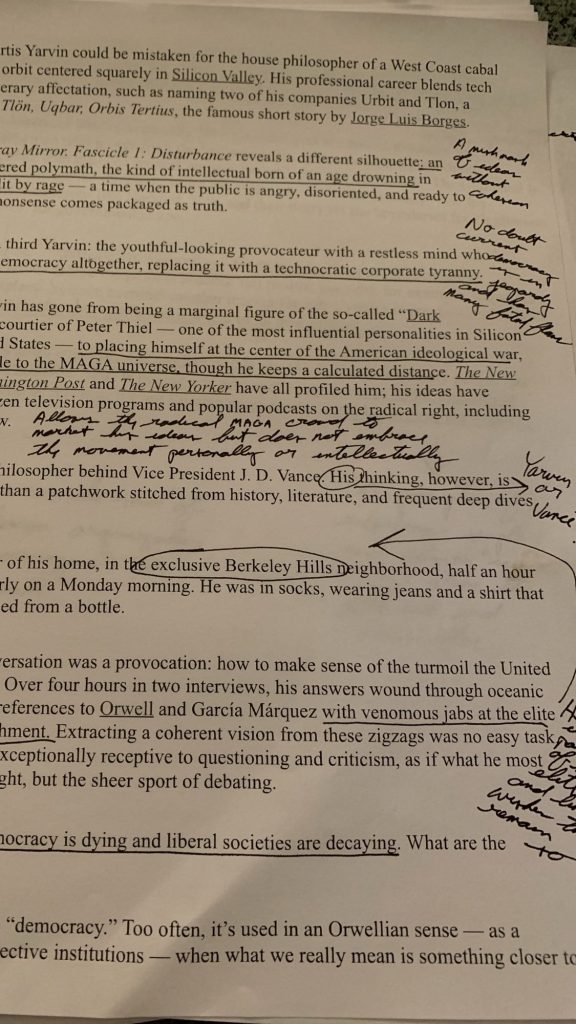

As one of the current darlings of MAGA’s upper echelons, my first impulse when I saw El Pais‘s interview with Curtis Yarvin was to immediately discount it as either a superficial piece of ego stroking or an extended game of cat and mouse where the mouse constantly hid behind thick panels of grandstanding and ad hominem attacks on enemies real or imagined. However, I did not yield to my initial impulse. Perhaps it was because El Pais is a left-leaning newspaper from Spain and I thought it might be freer from the kind of editorial cowardice we’ve seen from what passes for journalism in the United States. After reading the interview (carefully and with many annotations on my printed copy), I came to the conclusion I was not wrong about the newspaper and, to an extent, might be wrong about Curtis Yarvin.

Allow me to be clear: my only exposure to Yarvin’s ideas come from this one interview. It is possible that he, like many armchair philosophers embraced by political extremes, is conniving and modifies his message depending on the audience. I have not read any of his other works and have not even delved into his biography. Whether or not the views and notions he related in this interview are genuine, they still are worth considering and addressing. What this interview helped elucidate, at least in my mind, was some of the foundational issues Yarvin’s “CEO-authoritarian” or “corporate monarchy” seeks to address. I found a surprising amount of overlap between what most leftists see as problems and what Yarvin sees as problems, although the source of those issues and their possible solutions differ greatly.

Intersection

One thing in particular that I feel has been misrepresented by much of the mainstream media (and also overemphasized by his MAGA disciples) is the corporate part of the term corporate monarchy. The left hears this word and immediately imagines this means giving corporations rule over the country. I don’t necessarily see that as the objective, although I certainly can see how that could be a result. The idea that Yarvin seems to be pushing is structuring government in a corporate style — that is to say having a much more top-down approach where the leader (the CEO in this sense) is imbued with tremendous power that he or she will wield to “improve human flourishing, not to maximize GDP”. Again taking this remark at face value, it seems to align (at least in the desired outcome) with the stated aims of the political left. If we accept the possibility of a benevolent despot atop a corporation inspired government structure, the choice of ‘corporate monarchy’ as a name for this system becomes less frightening.

Yarvin, despite the attraction MAGA has to his ideas, seems to regard Trump as a kind of metastasization of societal decay rather than a messianic solution to it. Although he makes clear his disdain for the same non-specific rouge’s gallery of villains (e.g. Ivy League academics and the ‘deep state’), he also does not mince words when asked if Donald Trump can play the part of his idealized executive king:

No. Just look at his [Trump’s] record: he’s not a disciplined executive or an operational leader. The Trump Organization is all branding, not organization or real management . . . He’s [Elon Musk] a visionary, but not a manager; Trump lacks even the vision part.

This assessment, I feel, would be palatable and likely echoed by many of Trump’s most vehement critics on the political left. Similarly, his opinion of American conservatives’ current love-affair with libertarianism would likely resonate with many on the left. He calls the ‘marketplace as self-regulating’ idea a “myth” and “[t]otal fantasy”. Again, his words appear to contradict the profile presented of him by many MSM outlets as a champion of unfettered industrial power and subjugating the populace to the direct rule of Wall Street.

Even when the subject of immigration is broached, there is enough for leftists to agree on to make his vision worth listening to. Actually, there is widespread and bipartisan agreement that what passes for an immigration system in this country is not just broken but smashed and thrown into a shredder. There is no policy: only changes to enforcement priorities and rhetoric depending upon the interests of those in power. This allows Republican and Democrat, liberal and conservative, regimes to use migrants “as political weapons without [them] realizing it”. The left, arguably, uses migrants as a kind of weight to shift electorates’ balance of power in their favor over long periods of time. The right, in turn, demonizes migrants as a way to rally supporters around political schemes that ultimately benefit only the elites at the expense of vulnerable migrant communities and disaffected non-migrants alike. In the end, everyone is a victim of the completely and “fundamentally senseless” system.

This premise also applies to Yarvin’s assertion that:

[d]emocracy, as we know it, is dying. Its authority once rested on the mass’s physical strength, on the threat of revolt from the masses. Now, ‘the people’s’ power is symbolic.

Here again those of us on the political left can find a common denominator. Militant Republican gerrymandering in Texas, the White House’s occupation of the District of Columbia and the increasing inability of American courts to hold the executive branch in check have demonstrated that the ruling elite are operating according to their own whims. Elections have become largely performative as fewer people vote for fewer candidates. Storied newspapers, one-time bastions of journalistic integrity and backbone (like The Washington Post) have become personal blogs of the 0.1% and will stifle criticism if the masters of the universe demand it. This, as I said at the outset, was one of the reasons I looked to El Pais for an alternative perspective. Sadly, this is the democracy we have known for decades, so to say that this democracy is dying is effectively saying that the entire legend upon which the country was founded is dying as well. The supposed leader of the free world enables ethnic cleansing in Gaza and thinks Russia should be rewarded for invading Ukraine while applauding heavy-handed police responses against people protesting those actions — you do not have to subscribe to Yarvin’s ideas to acknowledge the truth in his words.

I must give credit to Yarvin for his mostly sober and reasonable positions and observations. The interview was probing and insightful on both sides of the table. The exchange resembled a kind of intellectual bullfight with Boris Muñoz charging at Yarvin with a piercing question, hoping to catch him unawares while Yarvin spun away at the last moment with a concession or counterpoint. At it’s conclusion, both bull and matador had put on a great show and both had emerged unscathed.

Diversion

With all that in mind, the interview also demonstrated just how theoretical Yarvin’s theory truly is. At the center of his corporate monarchy model is, of course, the monarch, a kind of supreme leader chosen by unknown processes and anointed by undisclosed hands. This corporate monarch would be responsible for ridding the country of needless complexities in law, politics, education and policy. He or she would untangle the bureaucratic ropes that, he alleges, allow the elites to create a sort of perpetual motion machine out of government — death by a thousand bureaucrats. The monarch will also be responsible for ‘realigning’ elite universities so that they are no longer the gatekeepers of scientific, social or educational orthodoxy. The Trump administration has taken this particular aspect of Yarvin’s model to heart and has very loudly threatened Ivy League institutions to adopt what amounts to intellectual affirmative action: coercing universities to give special consideration to ‘conservative’ ideas (i.e. ideas that conform to the regime’s definition of conservativism). The administration’s efforts on this front were, sadly, not addressed in this interview.

Attacking ‘elites’ has never truly gone out of style, but it has become particularly important for the MAGA movement. Even in this relatively short piece, Yarvin returns time and again to the claim that ‘the elites’ are gaming the system to further their own power and enrich themselves. Whatever truth there may be in these words, however, is dampened when you consider the person uttering them. Curtis Yarvin welcomed Boris Muñoz into his home in “the exclusive Berkeley Hills neighborhood, half an hour from San Francisco”. A quick internet search reveals that the average house value in that area is around $1.7m — not exactly palatial, but far above what many Americans will ever achieve. I don’t know what Curtis Yarvin’s net worth is and, for the purposes of this meditation, I have no desire to know. Even if we accept the possibility that he is ‘merely’ well-off, the fact that his ideas have percolated to the White House and the office of the Vice-President of the United States of America (J.D. Vance is often portrayed as a prophet of corporate monarchy) indicates that, whether he admits it or not and whether his bank statements show it or not, he is among the elite.

It can be argued, of course, that those who are inside the machine are the ones best positioned to dismantle it, but this interview demonstrated, at least to this reader, that Yarvin is more of a theorist than an activist, a storyteller rather than instructor. He did not strike me as someone eagerly awaiting the rise of the technocrat overlords — he seems like he is going to be comfortable in any case. He is not alone in his views that the bulk of the country is “caught between an exhausted institutional meritocracy on one side and increasingly erratic populism on the other” — I myself feel that neither the status quo nor Trumpism are good or viable options. There is also nothing new about his depiction of the United States as being both Red Empire (military and industrial domination) and Blue Empire (educating the future dictators of the word), squeezing the metaphorical toothpaste tube from both sides until the middle explodes.

When that happens, we see misguided anger towards very low-level members of the ‘bureaucratic elite’ (i.e. civil service) followed by the MAGA crowd cheering as Elon Musk rampages around Washington with his cadre of DOGE stormtroopers targeting the least elite people they can find. The Administrative Assistant to the Interim Director of the Subunit of the Office of the Department of the Interior’s Workgroup on the Preservation of the Greater American Moose is not the reason your groceries are so expensive or your health insurance is denying your heart medications or why you’ve been made redundant by AI. If we want to discuss the need for that position, let us have that discussion, but giving a gang of technocrat man-children the keys to the kingdom is both laughably foolish and wildly reckless. The true elites, the numerous high-level administration figures temporarily borrowed from Wall Street and Silicon Valley, remain in power and often are able strengthen their grip on power and increase wealth. While Yarvin himself might not have approved of such actions, his ideas were very much on the minds of those performing the actions and so he is at least indirectly responsible.

Even his notion of an enlightened dictator or benevolent despot is not exactly new, although we have given it new names and nomenclature. Machiavelli dedicated an entire volume to debating the risks and benefits associated with top-down rule and became an adjective as a result. Nowhere during this interview does Yarvin address such questions as how does the corporate monarch come to power; who ensures the monarch adheres to their mission; how is a corrupted monarch removed from power — the entire model is built upon a ghost, an illusory ‘noble dictator’ who is and always will be above and beyond reproach. This idea reminds me of the ‘reasonable person’ standard often employed by our courts, a mystical Everyman who is neither a fool nor a genius, neither too self-serving nor too altruistic. Such a standard is a fiction and, as such, can be represented in whatever fashion those in power wish. It’s one thing to say “[a] well-designed system has no reason to persecute people” and it’s quite another thing to lay out a plan for how such a system is to be designed. He calls out Dubai as an example of a place where:

“[y]ou can live freely under a dictatorship … You’re not free to challenge the system, sure, but you are free to live your life without fear, as long as you don’t try to change the regime.

This is an interesting definition of ‘freedom’ but one that’s not entire incompatible with the designs of corporate monarchy proponents. It also leaves unanswered the issue of how dissent would work in a Yarvinian society. Are we to believe that the supreme CEO will permit disagreement or protest? Will the ‘well-designed system’ ever require opposition? In a country long accustomed to partisan siloing and interstate friction, how will the corporate monarch go about uniting the populace under a single banner without the use of force? Again, Yarvin offers no details in this interview.

Conclusion

When you strip down Yarvin’s controversial worldview, what is it we see? Is it a genuine effort to improve the human condition in ways that existing systems either cannot or will not? Is it an insidious plot to create a new elite that can exert power more directly and not have to use proxies in Washington? Is it the deliberately inflammatory remarks of a Silicon Valley troll? Is it simply a thought exercise that has mutated in the hands of Trump’s close allies? Honestly, it is difficult to say based solely on this interview. As thought provoking as it may be, once you remove the literary references and the Latin, it is hard to glean any actionable details. In many respects, it seems like a long-winded way of saying the current state of things will lead to ruin and some alternative must be found.

There is a certain attractiveness in the idea of a Yarvinian technocrat operating the country mostly single handedly with the “goal … to improve the life of everyone — especially those with the least”. If we end there, this is a goal the political left would certainly endorse, even celebrate. However, Yarvin immediately uses China’s adoption of state capitalism as a kind of case study. While it’s true that this pivot probably represented the largest standard of living improvement in human history, the non-financial costs associated with that pivot (ecological and social) were also tremendous. It’s also not outrageous to believe that those tremendous improvements could easily reverse given the right combination of economic or social factors. It is, admittedly, natural to be envious of China’s ability to do in days what would take years in the bureaucratic morass we experience in the democratic West (e.g. the 1000-bed Wuhan COVID hospital that materialized in about a week). If a similar project were undertaken in the United States, even if granted carte blanche by the most anti-regulatory administration in the most industry friendly state, there is no way such a Herculean task could be accomplished so quickly, even if using the same prefabricated construction methods used in China. This kind of government response is the stuff of dreams in the western democracies where even minor changes in existing law can circulate through legislative committees and courts seemingly forever. Litigation is every bit a millstone on progress as government bureaucracy and the top-down approach we see in China is understandably seductive.

Perhaps there is a future where, as in the words of Donald Fagen, “[a] just machine [will] make big decisions; programmed by fellows with compassion and vision”, thus eliminating the need for a human techno-monarch. This might be the ultimate goal of the Yarvinites: developing an artificial intelligence system so complete that it can govern in purely analytical fashion and ignore disruptive and variable things like ideology or party allegiance. This too is a strangely attractive objective, but it ignores a critical reality.

My [Yarvin] point is you get bureaucracy, or you get top-down clarity, like the military or a well-run restaurant, which work in stark contrast to the way most current governments function. It comes down to hierarchy and mission. Systems work best when incentives are clear.

The analogy seeks to illustrate how this top-down approach works effectively, but it fails to appreciate the vast differences in size, complexity and diversity of thought between these organizations and the United States of America. Top-down autocratic systems can be effective (as in the army and restaurant examples), but this is mostly due to the fact that their incentives and missions are predefined and uniformity of thought and drive are almost a given. A Michelin star restaurant does not and cannot function as a democracy if it hopes to maintain that level of status — a country, particularly one as geographically, racially, economically, politically and culturally varied as the United States, is decidedly not a Michelin star restaurant and it is foolish to imagine it could peacefully be operated like one. We cannot agree whether Pepsi or Coke is better let alone agree on some all-encompassing roadmap to national prosperity under some corporate monarch. Perhaps this is where the idea of the network state comes in: a way of breaking apart the nation state into smaller, presumably more homogenous units, each ‘controlled’ (or managed) by its own techno-monarch. Yarvin does not touch upon the topic of network states and Muñoz does not pursue that line of inquiry so I will make no attempt to connect those dots.

I would not go so far as to say Curtis Yarvin is misunderstood: mistakenly deified by the extreme right, yes, but not misunderstood. He is quite frank that his model would completely alter everything we have ever thought, felt or learned about the United States. Although he presents this vision as a way to avoid bloody revolution, it is difficult to see how such a radical departure from the country’s current trajectory would not result in at least pockets of violent resistance. However, ten years ago we would have never dreamed that a thrice married, New York elite libertine would have such a devout following among Americans who make a point of condemning morally bankrupt big city elites. Maybe, if given the right king to kneel before, the ‘Don’t Tread on Me’ flag wavers would be willing to lay down and get some shoe prints on their backs.